Hunger challenges exposed by the pandemic

Food banks and pantries forced to rethink delivery of food to rising numbers in need

By Michael Crumb

“Without food, you don’t have anything.” Tara, 43, of Des Moines.

Tara, who lives with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, an inherited connective tissue disorder that has left her unable to work, has been receiving help from food pantries and federal food assistance programs since 2014 after reaching out to the United Way of Central Iowa and the Des Moines Area Religious Council. Walking into a food pantry for the first time, she felt a restored sense of hope after years of feeling lost.

“I remember walking into the pantry … and someone making eye contact with me and saying, ‘Hi, how are you,’ and I just kind of froze because I wasn't sure how to respond to that because I was so used to people treating me more like an animal than a human being at that point,” said Tara, whose last name is being withheld for privacy. “I just remember that I felt dead inside for so long. I just remember feeling like, OK, someone sees me, this is real. I still have value, I still have hope. I think that's when my hope kicked in. I just needed one person to see me, and to let me know ... you're not going to starve to death. You matter. Food is important.”

Iowa Stops Hunger

Business Publications Corp. and its publications — including the Business Record, dsm Magazine and ia Magazine — have launched a yearlong campaign, Iowa Stops Hunger, to bring attention to the plight of those who are food insecure, and to shed light on those who have made it their mission to help.

Over the next 12 months, we will facilitate conversations about food insecurity through the words of those people on the front lines, fighting each day to help feed those who are most in need in our state. We will strive to tell the stories of those who, all too often, are forced to make tough decisions about feeding their family. And we hope that over the next year we will inspire you to get involved to join us and seek answers that can lead to change.

Food insecurity and food banks

Food Insecurity is simply defined as not having enough healthy food to eat. It’s an economic symptom, not a physical condition, such as hunger, although the terms are often used interchangeably. It is also linked closely to other social conditions affecting the low-income and those living in poverty.

What was already a seemingly insurmountable challenge has only worsened in recent months as the coronavirus pandemic tightened its grip on the state and the country, with shutdowns, layoffs and furloughs. It’s forced many who had never visited a food pantry or applied for food assistance to seek help for the first time.

Food banks are the central collection point that distribute food to food pantries in their area, and as the need has increased, they have had to quickly adapt, said Michelle Book, CEO of the Des Moines-based Food Bank of Iowa.

“What’s changed the most is everything we do,” she said. “We have had to rethink everything. We have redesigned how we get food out to food insecure Iowans.”

Mike Miller, CEO of Riverbend Food Bank in Dubuque, said his operation has seen demand jump 36% in recent months. At the same time, the supply chain has seen interruptions caused by the pandemic, forcing the food bank to increase spending by 50% to purchase food to keep its shelves stocked, all while adjusting its operation to keep staff and clients safe.

“We have to balance using resources to meet this need immediately, and we don’t know how long this will last,” Miller said. “We’re going to be stretching it out over the long haul. This is a marathon, not a sprint.”

Food bank operators said grocery stores, a good source for food banks, have had trouble keeping up with demand from shoppers, creating interruptions in the supply chain. Another challenge was that some events, such as food drives by groups like the Boy Scouts, couldn’t be held because of the pandemic, further reducing supplies coming in to fill food bank shelves.

Nearly 600,000 Iowans -- or almost 1 in 5 -- have experienced food insecurity in recent months, an increase of about 67% since the coronavirus pandemic arrived in Iowa, according to data from Feeding America, a network of 200 food banks across the country. Nationally, that number has risen from 37 million people before the pandemic to about 54 million today.

Linda Scheid, executive director of Food Bank of Siouxland, in Sioux City, said what was a crisis before has only been placed in the spotlight by the pandemic.

“The pandemic has exposed the hunger problem,” she said. “There was a hunger problem … for many years, but the pandemic kind of brought it up to the top of people's consciousness.”

Scheid said one of her primary concerns is how to maintain the level of service that has been needed in the past several months for the long term.

The food bank’s largest month to date had been 275,000 pounds of food distributed in October 2019. When the pandemic hit, they surpassed that by 43%, distributing 300,000 pounds in March, Scheid said.

Despite concerns that donations would fall off because of the pandemic, people have stepped up in recent months, she said.

“Those with the capacity to give are a little more selective, and they’re going to focus on the things that are most critically important at this time of crisis,” she said. “So we’re out there telling the story and telling people we were here last month, last year, the last 10 years, the last 20 years, and the response has been amazing.”

A complex problem with no easy solutions

To understand the issue of food insecurity, one needs to know the social complexities of it.

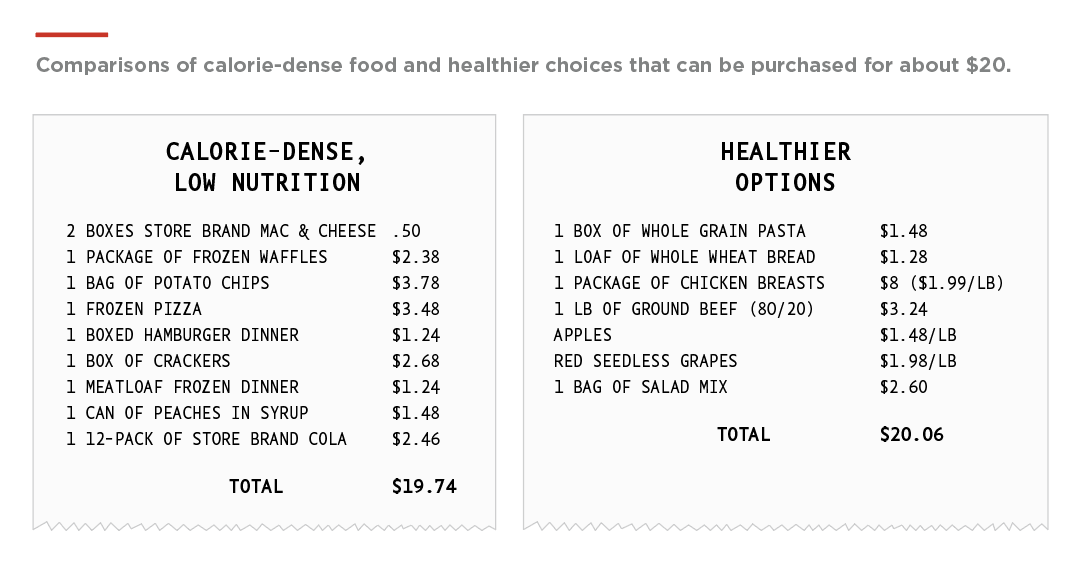

First, to be insecure doesn’t always mean someone doesn’t have enough food to eat. Too often, it means because a person is low-income, the choices they make are calorie-dense and low in nutrition, and that can often lead to health problems, such as obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

Second, because it is so intrinsically linked to poverty, food insecurity is more often seen among those with the lowest incomes, and it frequently follows the trail of racial inequity that is all too common in our community.

As the pandemic has hit communities of color the hardest, that same inequity is showing up in food insecurity, said Matthew Canfield, a cultural anthropologist at Drake University.

“If we look at who is hungry in the United States, it matches a lot of racial disparities,” he said. “If you look at the coronavirus, 39% of Black families are food insecure as a result of the pandemic, whereas whites are at 22%.”

Canfield said the issues found in food insecurity reflect two major issues in the U.S. One, he said, is the transformation of the economy and increasing income inequality. That has led to a huge expansion to meet the need for food assistance, he said.

Canfield said another issue is with the nation’s food system.

“Our food system is based on large-scale industrial agriculture, in which the cheapest calories are the most unhealthy,” he said. “Often, when we think about food insecurity, you think about not having enough to eat. But one of the things we also see is rising rates of malnutrition, and particularly when we talk about diet-related illnesses, like Type 2 diabetes and obesity.

“So those issues of structural inequalities in our economy, and the kind of food system that is geared toward cheap calories that are also the most unhealthiest, are the major drivers of food insecurity in this country.”

Food deserts

There are an estimated 55,000 people who are food insecure in the Polk County area, according to Feeding America.

Luke Elzinga, communications and advocacy manager of the Des Moines Area Religious Council, or DMARC, said access is one factor that leads to food insecurity. DMARC is an interfaith organization that operates a food pantry network to help those in need.

Elzinga said even cities like Des Moines, the state’s largest, have food deserts, or areas that don’t have a grocery store readily accessible.

“If you look at the map of full-service grocery stores in the Des Moines area, they skew more towards the suburbs,” Elzinga said. “If you have transportation barriers and you don’t have a vehicle, and you’re relying on a bicycle, walking or a bus, that makes it that much more difficult.”

Elzinga said a convenience store may be close by, but a grocery store where healthier food choices are available may be beyond someone’s reach. There are three census tracts in Des Moines that are food deserts, mostly on the city’s northeast side, he said.

Another factor, according to Luke Lynch, opportunity director of United Way of Central Iowa, is that infrastructure that exists in higher-income neighborhoods is often less prevalent in lower-income areas.

“It’s also about access to bike paths, walkable bike paths,” he said. “So not only are there not as many stores, there’s not a good way to get out and get to those locations where healthier food can be found.”

A hidden population

According to Lynch, 22% of people in Central Iowa are considered income constrained, which means they may work two or three jobs and still struggle to pay their bills. And that number, he said, has likely grown with the coronavirus pandemic.

“When people say they don’t see [food insecurity], well, they do see it,” Lynch said. “These are people working at convenience stores. These are people working on the front lines, working those minimum wage jobs, and [maybe a] few of those minimum wage jobs, but they still find themselves in poverty.

“It’s right in front of us,” he said.

Lynch said the United Way of Central Iowa uses a threshold of 250% of the federal poverty level when considering whether someone is financially self-sufficient. That means a family of four making as much $65,000 a year could find themselves struggling and experiencing food insecurity, he said.

Food insecurity crosses many job sectors, and can affect a person’s performance at work, Lynch said.

“It’s hard to let go of that struggle,” he said. “If they come to work and they are experiencing a struggle at home and they have to worry about that, how productive is that person going to be?”

Overcoming the stigma

Elzinga said all too often people don’t see food insecurity because the people who are experiencing it usually don’t want to talk about it.

“It’s hard to get people to share their experiences because there is a sense of shame, and that’s largely due to society pressures,” Elzinga said. “People feel like if they aren’t able to provide for their family that they personally have failed rather than seeing failed policies.”

Elzinga said getting people to tell their stories to organizations like DMARC -- which has a Storytellers Committee to host workshops where people can develop their stories to share with elected officials and community leaders -- may help.

Unfortunately, that was put on hold because of the pandemic, he said.

“We feel like if we can get that process going, if we can help people share their stories, that in itself can help reduce the stigma,” Elzinga said.

Tara, the Des Moines woman who receives assistance to make ends meet, said no one should shy away from seeking help when they need it most. “I would tell them there is no shame,” she said. “I let people know that they're never alone.”