Manager Garren Zanker is a familiar face at Jewell Market, about 20 miles north of Ames. Photo by Emily Kestel

Restocking the shelves

Two Iowa towns rally to save their beloved grocery stores

By Emily Kestel

Jewell, a town of 1,200 in Hamilton County, has a dozen retail stores, two banks, a few salons and chiropractors, a library, dentist office, medical clinic, hardware store, co-op and a public school district.

But a few years ago, the town almost lost one of its most essential businesses: its grocery store.

The owner of what was then called Heartland Market, who also had a handful of other grocery stores across the state, locked the doors and closed up shop in January 2020.

Board members of the Jewell Area Development Enterprise knew something had to be done to reopen it.

“I was adamant, we have to have this,” said Mischelle Hardy, president of the JADE board and owner of Sew Bee It. “People don’t want to live in a community that doesn’t have the essentials.”

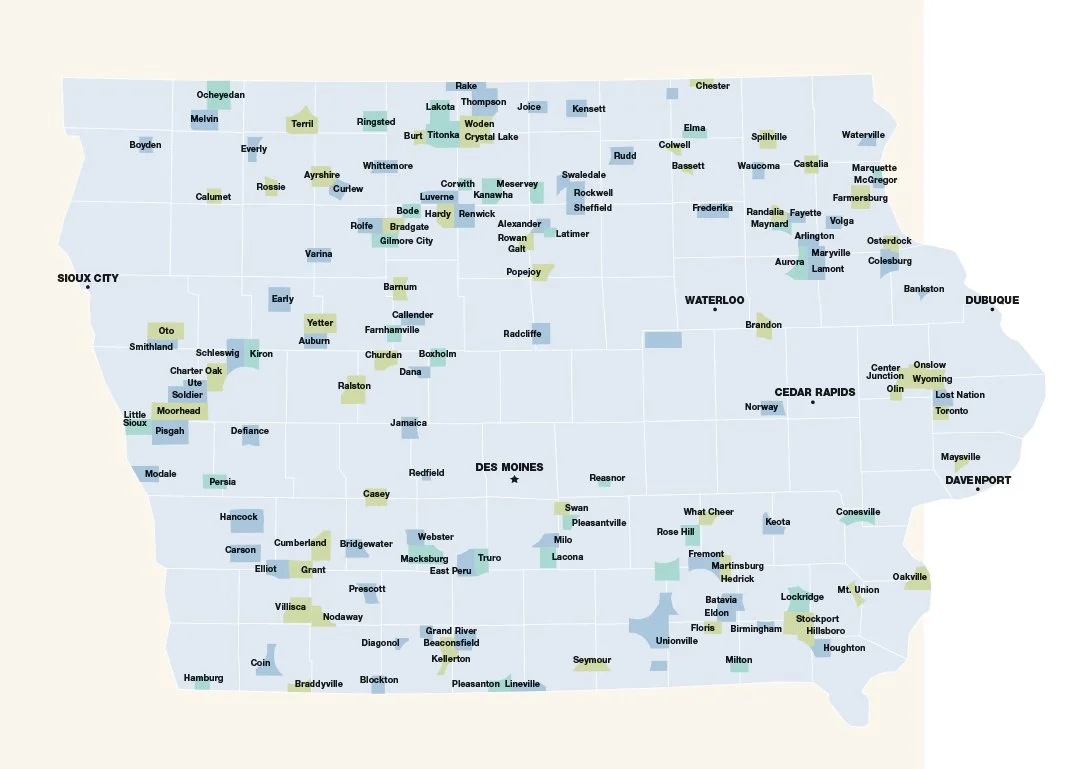

Map Data: Jordan Burrows, University of Northern Iowa

Rural food deserts in Iowa without food pantries

In 2022, the University of Northern Iowa published a statewide map of rural areas where at least 10% of locals live in poverty and without access within 10 miles to a wholesome food store or pantry. The poverty line for an Iowa family of four correlates with an annual household income of $30,000.

Mapping Iowa’s food deserts

With nine municipalities within its borders, Hamilton County has a population of 15,000. According to recent data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the county has only four grocery stores, two of which are in Webster City.

In the first half-year after Heartland Market’s closure, Jewell qualified as a “food desert,” which the USDA defines according to two criteria: low access, where the closest supermarket or grocery store is at least 10 miles away, and low income, where the median family income is at or below 80% of the statewide median family income.

Jewell residents had to drive 30 minutes to get their groceries in Webster City or Ames, a hindrance for everyone, especially for residents who are elderly or can’t drive.

After hearing about food deserts in a geographic information systems class at the University of Northern Iowa, Jordan Burrows, an environmental intern at the Iowa Waste Reduction Center, created in March 2022 a food desert map that shows where Iowa’s largest gaps in access to healthy food are.

First, she identified where all of the state’s chain grocery stores are, including Hy-Vee, Walmart and Fareway. Then, using Google Street View, she went into the empty spaces on the map to see if the communities had a hometown grocery store. She also took food pantries into account. From there, she used a buffer tool to create 10-mile radii, which indicated the remaining gaps, shown on the map as colored polygons.

In total, 111 communities in Iowa are considered food deserts, according to Burrows’ methodology. If food pantries were excluded from the calculation requirements, 43 more communities would be food deserts, boosting the total to 154. While she knows there’s room for error, she wanted the map to help people see how many areas in Iowa lack access to healthy food.

Contributing to the increase of food deserts in the state are the closures of small, independent grocery stores.

A spokesperson for the Iowa Grocery Industry Association said there’s been a 15% decrease in the number of independent stores within its membership base in the last 10 years. Between 1995 and 2005, 43% of grocery stores closed in Iowa towns with fewer than 1,000 residents.

“Iowa grocery and convenience stores, including independent stores, face challenges of declining populations, fierce competitive landscapes, razor thin profit margins, and changing industry trends like online shopping,” Iowa Grocery Industry Association President Michelle Hurd wrote in an email. “Grocery and convenience stores are essential to Iowa towns, providing access to safe, fresh and healthy food while also providing jobs and fostering economic resilience for their communities.”

Rallying for a cause

Following the closure of Heartland Market in early 2020, the Jewell Area Development Enterprise board created an LLC and hosted several public meetings at the local country club to discuss how to get the grocery store back up and running.

The result: In May the city of Jewell purchased the building for $75,000, according to public records, which JADE board president Hardy called “a blessing.”

To help cover the costs, the JADE board decided to make the new grocery store a community-owned market, in part by selling shares for $400. With an initial goal to raise $220,000 — enough to pay for new shelving, inventory, repairs and several months of routine expenses — the board hosted several fundraisers, sold more than 300 shares and gave a $20,000 matching grant. After a few months, their goal was met.

On July 8, the store reopened as Jewell Market.

It’s a popular spot to grab lunch. Daily specials of ham balls, stuffed peppers, chili, burgers, pork tenderloins, orange chicken or twice-baked potatoes can be found on any given menu, which the South Hamilton Record-News publishes in a weekly advertisement. Farmers, teachers and business owners alike often stop by for a bite to eat.

More than that, the store is a simple check-in spot. Manager Garren Zanker knows the name of just about everyone who walks in. He’ll say hello and ask them how things are going.

It’s an especially welcoming environment for entrepreneurs. Zanker sells a plethora of local products. His high school classmate’s wine, eggs from another classmate, honey from a classmate of his seventh grade son, and summer sausage, pork sticks and bologna from his brother’s meat locker — they all have a spot on the shelves.

The store helps out those who need it most. Through a partnership with the Lord’s Cupboard program at nearby Bethesda Lutheran Church, anyone who needs food can bring in a signed voucher and walk out with a free bag of qualifying items: potatoes, ground beef, milk, bread, butter, eggs and $10 worth of fresh fruit and vegetables. Zanker also invites customers to buy a $20 grocery bag, and the store will fill it with food to give to a South Hamilton Elementary School family in need.

It’s a fundraising hub, too. Since 2020, Jewell Market has hosted more than a dozen fundraisers. One helped a family whose mother had died in a farm accident. Another supported a woman who was battling cancer. One more helped the Jewell Fire Department buy rescue boats, following the death of two Iowa State University rowing club members at nearby Little Wall Lake.

If you walk through the front door of Jewell Market and head straight back to the meat counter, you’ll see a framed photograph hanging on the wall by the exit sign. In the photo, dated June 14, 2020, is a long line of cars that looks like the final scene in “Field of Dreams,” snaking their way through town for a pork loin lunch that raised funds for a family whose house caught on fire.

The photo serves as a reminder that Jewell Market is much more than your run-of-the-mill grocery store. “It’s a town hall, a center square,” Zanker said. “There’s a greater sense of community and helping people out when they need it.”

And that, he said, is Jewell’s secret sauce.

Tom Mulholland, owner, Mulholland Grocery in Malvern, stands where his family grocery store used to before burning down in December. Photo by Emily Kestel

Rising from the ashes in Malvern

Tom Mulholland will always remember Christmas 2021 as the one when he felt like George Bailey from “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

On the evening of Dec. 13, his grocery store in Malvern, which had been in the family for four generations, burned down. It took firefighters from more than 25 communities in southwest Iowa to put it out. In doing so, they completely drained the town’s water supply.

Two days later, high winds knocked down the only brick wall left standing from the fire.

“Words cannot express the gratitude for the love and support I have been shown,” Mulholland wrote on Facebook after the fire. “The way that people have shown their care and have also given so generously has made me feel like the richest man in Malvern.”

He still gets emotional thinking about how quickly the donations and words of support poured in.

For nearly 150 years, Mulholland Grocery was a fixture in the town of about 1,000 people. Opened in 1875 by his great grandfather, Mulholland’s had a reputation for having the best meat counter in the area. Tom Mulholland said he had regular customers from Ames, Omaha, Lincoln and even St. Joseph, Mo.

He bought the store in 2008, after managing a grocery store in Omaha for 20 years. Mulholland’s had been out of the family for 17 years with three different owners before Tom came back.

When the store burned down, the community immediately felt the impact. The next closest grocery stores are in Glenwood, Red Oak and Sidney, all between 15 and 30 minutes away.

Beyond the obvious inconvenience, Mulholland said living in a food desert has other effects. When people shop for groceries only a few times a month, they tend to rely on canned, frozen or boxed products, instead of fresh options. Over time, that has an impact on health and nutrition.

Folks who shop for groceries out of town are also more likely to run other errands there, too, which leaves hometown pharmacies, hardware stores or clothing stores hanging.

“In the time that I’ve owned my store, within 45 miles, six communities have lost their grocery stores,” Mulholland said in a recent documentary sponsored by Meta. “When a small town loses their grocery store, that’s just the beginning of the death spiral for that community.”

Even so, the decision to rebuild wasn’t an easy one.

Just before the fire, he and his wife divorced. The year following the fire, he suffered a number of freak injuries. He broke a toe. He tore ligaments in the bottom of his foot. He tore a muscle in his leg. A tendon in his bicep snapped. He herniated a disc. The pain was so bad, Mulholland said he contemplated suicide.

Any other person would look at that and think it was a sign from God to quit.

Mulholland said he thought long and hard about what it would take to rebuild. He looked at all sides. On one hand, he was getting old and was hoping to retire soon; he celebrated his 63rd birthday this spring. On the other hand, if he didn’t rebuild, all he’d get from insurance would be what the building was worth – he bought it for $60,000 in 2008 – plus the value of its inventory, up to $200,000. That wouldn’t be enough to retire on.

So the more he heard friends and neighbors talk about how much they missed the store, he made up his mind. “If I don’t do it,” he said, “this town will never have a grocery store again.”

Now, when he looks down at the pit where Mulholland’s once stood, he sees a future.

“Especially now that the town realizes how much they miss it and what it meant for the community,” he said, “I expect things to grow bigger than they were before.”

He hopes to open the new 5,000-square-foot store by May 2024.

“I care about the future of this community,” he said. “Being able to put a grocery store back here is going to mean so much more in five, 10 years for all of the businesses.”

No doubt, George Bailey’s guardian angel would agree. “Strange, isn’t it?” he mused in the movie. “Each man’s life touches so many other lives. When he isn’t around, he leaves an awful hole, doesn’t he?”